My wife and I met in 2001 and five years later were married in a dream ceremony at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, Italy.

A year later, we were pregnant with our first child and on May 25, 2008 – a day after my wife’s birthday – our daughter entered the world, albeit six weeks early. My wife was diagnosed as gestational diabetic during the pregnancy and unfortunately, following the delivery, she remained diabetic. Thankfully, she was able to manage her condition through diet.

In early 2009, we were pregnant once again, but unfortunately, we lost the baby at 16 weeks. Needless to say, we were very devastated by the news. We made the decision to try one more time while time was somewhat on our side. I was 43; she was 42 – and diabetic.

We were blessed later that year with the news that we were once again pregnant. We were advised to get monthly progesterone shots to ensure that the uterine conditions were conducive to carrying the pregnancy to full term.

The pregnancy was difficult, with my wife losing her appetite and experiencing persistent diarrhea and extreme swelling in the joints, mainly the extremities such as her fingers and ankles/feet/toes especially in the second trimester. Additionally, she was unable to find comfort in sleep and spent many restless nights in the living room watching TV.

In January of 2010, during a routine visit to our GP with a cold, my wife passed out and was subsequently treated for dehydration in the ER. Her numbers checked out fine but this was to prove a warning shot over the proverbial bow of our ship. Later in June, my wife’s blood sugar levels became unmanageable by diet and she began taking twice daily insulin shots.

On June 28, during a visit to her OB/GYN, we were informed that her regular OB of five years had resigned from the practice and that her case would now be taken over by the principal partner in the practice. During his routine questioning, my wife disclosed a shortness of breath. She was 5’6″ and had already gained about 40-50 pounds with a due date of around August 8th. To his credit, our new OB was not happy with this info and immediately referred her to the ER.

Upon admission to the ER, she was diagnosed with critically low potassium levels (approx. 2.3) as well as abnormal magnesium levels. She was immediately admitted to the hospital and started on potassium drip therapy and intermittent magnesium drip therapy. To compound matters, her blood pressure had risen and her blood sugar levels began to elevate.

As we were entering the July 4th holiday period, we discovered that her endocrinologist was on vacation and that there was no backup at the hospital during his absence, and therefore her case would be handled by her GP and OB. Also, the new OB was now on vacation and passed her case on to his partner…essentially, her second new OB in the space of two days.

Over the course of the next three days, my wife received a total of 18 units of potassium and approximately four units of magnesium. Additionally, they played with her insulin levels, at one point increasing it four-fold over what her normal daily injections had been.

Unhappy with the “threat” of a PICC-line and four more days of hospital stay, we eventually requested to be moved to the high-risk women and children’s hospital in town. On July 1 at approximately 6 p.m., we were finally granted the transfer – against the wishes of her “new” OB.

Five hours later, as I was about to settle into bed with our daughter at home, I called my wife one last time to make sure she was okay and was informed that I should put sleep on hold as it appeared that she was going to be discharged. Whereas the previous hospital (not high-risk) had wanted her to achieve a potassium level of 4.0, the high-risk hospital was fine with a level between 3.5-4.5, which she had finally achieved. She was told to go home, given a prescription for potassium pills, told to do a 24-hour urine collection and asked to return to the hospital on July 3 to have her urine tested for protein and to have her potassium levels checked again.

Everything checked out on the 3rd but she was advised to schedule an appointment with the high-risk OB as soon as possible – but not STAT. Upon calling said doctor, we were told the earliest they could get her in was 11 days later.

On July 14, my wife visited the high-risk OB and was told that her blood pressure was 171/95. She was diagnosed as severe preeclampsic and immediately admitted to the hospital while being told that they might deliver the baby that evening though they would try to manage her blood pressure and give the baby more time to develop. He was 35 weeks and four days at that time. Her BP never improved below 154/90 and our baby boy was delivered successfully via C-section without complications on July 16. All along, we were told that the cure for preeclampsia was delivery.

48-hours later on July 18 (Sunday), my wife was cleared to go home. As she had had her pre-requisite bowel movement that morning and her vitals were deemed acceptable (BP now at ~140/85), she was discharged with the usual spiel on caring for the C-section wound site and taking care of the child. No mention was made about the threat of post-partum eclampsia. She was told to schedule an appointment with her OB for that Friday, with no additional follow-up scheduled in between.

We returned home to find our daughter had a cold. On Monday afternoon, my wife began to complain of shortness of breath – not being able to get a full breath. We passed it off as normal for someone who had just had a C-section, combined with milk-laden breasts. On Tuesday, I returned to work for a team exercise while my wife made a visit to the pediatrician with our daughter and her brother. She was again experiencing shortness of breath and was finding every step to be a struggle.

That evening we went to bed at around 11:15 p.m. About an hour later, I was awoken by her and was told that she “needed my help.” Quite groggy, I took a moment to get my bearings and then accompanied her into our kitchen. When I asked her what was wrong, she said she couldn’t breathe – and the situation quickly devolved into what appeared to be hyperventilation, accompanied by extreme anxiety and fear. I tried to calm her, but it just increased to the point that I called 9-1-1, having determined that it was beyond my scope of understanding.

I stayed on the phone with the dispatcher for seven painful minutes while my wife went from a seated-on-the-chair position to a seated-on-the-ground position to a laying-on-the-ground position. At the same moment that the paramedics arrived, my wife stopped breathing and began to turn blue. Though the paramedics tried in vain to get a pulse and start her breathing again, they ultimately left the house performing CPR on her, heading to the hospital only five minutes from our house.

Upon arriving at the hospital, I was told that they had managed to regain a pulse after 25 minutes but that my wife had most likely suffered severe brain damage from the lack of oxygen. Their prognosis for recovery was grim, with little hope given for any meaningful recovery. For all intents and purposes, my wife had died in my arms on our kitchen floor, her final words being “I love you.”

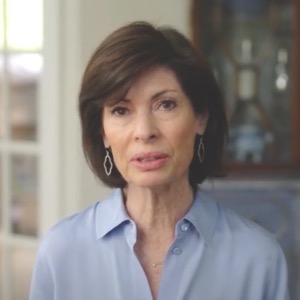

Joan stayed with us for 17 days. Her family – her mother, father, sisters, brother and numerous nieces, nephews, friends, and in-laws – were by her side constantly, providing a 24-hour vigil and soothing her as best they could with prayers, music, and conversation. She never regained consciousness and on August 6, three days after being removed from life support, she passed away. The silence since then has been deafening.

According to the coroner, her official cause of death was determined to be post-partum eclampsia, a disease that many doctors refuse to acknowledge as real. In fact, consultations with five medical experts after her death yielded five different points of view on how her collapse came about. Not a single one would corroborate the findings of the coroner.